Injuries of the finger tendons are common in rock climbers. The onset of your injury might be sudden or slow, and in the latter case, it might be hard to pin down the origin of your pain. In any case, the finger tendon injury that’s seen most often in rock climbers is tenosynovitis. This is an inflammation of the tendon sheath.

If you think you have a finger injury it could be an injured tendon but not necessarily. Other common injuries in the fingers of rock climbers are pulley (annular ligament) injuries, cruciate ligament injuries, capsulitis, and epiphysial fracture. The latter is common in youth climbers between the ages of 10 and 15.

With that being said, let’s dive into the 5 finger tendon injuries that are seen in rock climbers.

1. Tendonitis/Tendinopathy

Tendonitis is an inflammation of a tendon, but tendonitis is often used to describe pain in a tendon as well. Still, not all tendon pain is caused by inflammation and thus a better way to describe pain arising from a tendon is to call it a “tendinopathy”, or in layman’s terms, a diseased tendon. These conditions of a tendon have a slow onset and are therefore easily differentiated from tendon tears and ruptures which are caused by acute high-velocity incidents. I describe tendon tears in more detail below.

Now we got that clarified, let’s have a look at how tendinopathy in the finger tendons occurs.

A tendinopathy is always a result of overload. For rock climbers an overload of the finger tendons can be generated in a variety of ways, among them are:

- Crimping unnecessarily

- Inefficient grip-use

- Taking too few rest days

- Movement deficiencies in the upper extremity are then compensated in the fingers

- Hypertension in the forearm flexors

Each of these issues causes an overload on the tendons in the fingers. Since tendons have relatively little blood circulation their metabolism is slow. This causes an overload of the tendon to have a delayed effect which is why you only notice your tendinopathy after several weeks of overloading, unlike the loading of a muscle for example, which will tell you within 2 days after exercise how hard it was.

The building blocks of tendons, tenocytes, respond to load and if you train correctly, they will build strong tendons. If you overload, however, there’ll be more breakdown than the construction of new tendonous tissue.

The best way to deal with tendinopathy in your fingers is by resting if the pain is aggravated or if there’s active inflammation. Then after 2 weeks, you can start a loading program that focuses on stretching the tendon, both passively as well as with exercises emphasizing the lengthening (eccentrics) of the tendon. How fast, or slow, this loading plan progresses is highly individual.

2. Tendon Tear

A tendon tear and a rupture are both acute injuries. These happen usually because of a high-velocity accident. A fall, a slip, or a hold breaking off. Still, if you have been overloading your tendons for a period there’s a chance that microtraumas accumulate in your tendons. This in turn will weaken your tendon and increase the chance of tendon tears or ruptures.

There are roughly 3 categories of tendon tears:

- Tendon strain: the tendon is damaged, but no fibers are torn

- Partial tendon tear: the tendon is damaged, and fibers are torn

- Complete tendon tear: the tendon is completely torn. Depending on which tendon it is, as well as on your future climbing goals, surgery might be indicated but is not always necessary. A complete tear of the supraspinatus or long head of the biceps tendon is often treated conservatively.

After a tendon strain, you can expect to return to climbing within 6-12 weeks. After a partial tear, count for up to 6 months which also counts for a complete tear that’s treated conservatively. If you do surgery though it might take between 6-9 months. Remember, that these are indicators and not laws. It’s best to look at functional benchmarks to get a realistic idea of your readiness to return to rock climbing after a tendon tear. Functional benchmarks are:

- Pain

- Active range of motion

- Strength

- Stability

- Coordination

Each of these can be tested and compared to your healthy side to get an idea of your progress. This is better than just following a set protocol that is based on time. Still, comparing sides is not perfect either. Because the side you compare with might not be sufficient either. The best way to compare your functional benchmarks would be with a database of scientific data with numbers that correlate with healthy climbers for each grade. As far as I know, there are datasets like these for handball and soccer, but not for climbing, unfortunately.

The best way to treat a tendon tear is to start with a couple of days of rest and then start a loading program with a lot of stretching. This will ensure your tendon fibers consolidate in the right direction and will recover (almost) all their original strength.

3. Tenosynovitis

A tenosynovitis is an inflammation of the tendon sheath and is caused by overload. After injuries to the pulley ligaments, tenosynovitis is the most common finger injury in rock climbers.

Since tenosynovitis is inflammation, you might find that your finger is swollen, painful, red, and warm. The best way to treat tenosynovitis effectively is to start by unloading it. After a period of absolute rest, you can start stretching and commence a loading program focused on eccentrics (the muscle-lengthening part of an exercise).

To fight the inflammation a doctor can prescribe you anti-inflammatory drugs. Once the inflammation is gone, I have had good experiences with radial shockwave therapy (RSWT). Even though there’s no conclusive scientific evidence on how effective RSWT is and how it works – it has been widely accepted as a valid treatment for tendon injuries. My personal experience is that it usually works within a couple of treatments. If nothing happens in those first treatments, it’s better to not invest any more time in it.

If you treat tenosynovitis right away, you might return to climbing within 3-4 months.

4. Ganglion

A ganglion is a piece of connective tissue that grows onto your joint capsule, pulley ligament, or tendon sheath. Because of microtrauma, a ganglion can form at the injury site. In climbers, they’re common not only because of the high load on the fingers but also depending on the type of holds you grab. Small pockets and sharp edges can also provoke microtrauma. The onset of pain due to a ganglion is slow.

Ganglia is are sometimes easy to feel but at other times hard to diagnose. In that case, it’s best to use ultrasound sonography to see if a tendon sheath ganglion is at the origin of your pain.

Normally you treat a ganglion conservatively with rest, protection, and an alteration of your climbing. Evading movements and holds that provoke pain and/or protecting the ganglion with tape or plastering.

5. Extensor Hood Syndrome

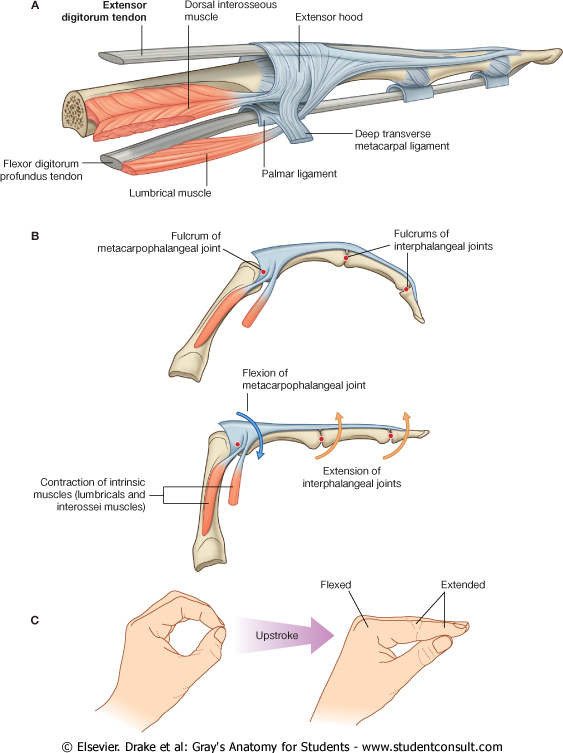

Extensor-Hood-Syndrome is an irritation or inflammation of the tissue by which the extensor tendons connect to the fingers. Each tendon morphs into an extensor hood which then wraps around the respective digit. When the joint surfaces of the phalangeal joints have degenerated because of osteoarthritis, osteophytes can grow along the joint edges. These are bone spurs that develop due to increased friction in the joint surfaces that then irritate the extensor hood.

The onset of the pain on the dorsal side of your fingers will be slow and is more likely when you’re above the age of 50. It’s unlikely that if you’re below 35 that Extensor-Hood-Syndrome is the origin of your dorsal finger pain.

The best way to treat Extensor-Hood-Syndrome is by adjusting your climbing intensity and looking for positions and movements that are pain-free. Spending more time in these positions ensures blood flow to the finger joints without irritation. Besides, traction of the finger joints can help you to reduce pain and stiffness. Otherwise, I recommend that in combination with reducing your climbing intensity you start a loading program guided by your pain to get back to your original climbing intensity. If pain persists you can consider taping the finger joint that hurts to prevent it from going near positions that irritate.