As a beginner, it will be optimal if you can climb 2-3x/week. Take at least a day between training sessions, as this provides repeated stimuli to your tissues and nervous system without sacrificing recovery times.

To understand completely why and how you should climb as a beginner it’s important to grasp the time your mind and body need to adapt to this new way of moving. And all the physical risks that come with it. That’s why in this article I’ll discuss subjects such as soft tissue adaptation, recovery times, and skill development so that you can make a well-informed decision on how and how often you should climb as a beginner.

Are you ready?

Let’s get right to it!

1. Connective Tissue Adaptation

Connective tissue adaptations are changes in your connective tissue due to new forms of loading. In this case, you started rock climbing.

Connective tissue is found in all your bodily tissues. The following tissues are essential structures for rock climbing:

- Bones: the foundational structure of our body

- Ligaments: taught bands that limit extreme joint movements

- Tendons: connect muscles to bone

- Muscles: move bones and thus generate movement

- Neurons: transmit electrical signals from the brain to the body and vice versa

- Cardiovascular system: pumps oxygen to your muscles as fuel and takes waste products away

Each of these structures will adapt to rock climbing in its way.

Here’s an overview of what must happen to each of them:

- Bones must get stronger to support you falling from boulder problems and flying into the wall after a fall on sports routes. The bones of your feet need to become resilient against the altered specific forces of wearing climbing shoes. Furthermore, your bones need to resist the novel forces tendons transmit from the muscles. Mainly the tendons that connect the upper limb muscles to the finger, hand, lower arm, and upper arm bones.

- Ligaments must become stronger and more resilient to stretching to be solid in end ranges. Most importantly the annular ligaments of the fingers so you don’t get pulley injuries.

- Tendons need to become stiffer to efficiently transfer force from muscle to bone. They also need to become stronger to deal with higher loads. This applies mostly to the tendons that connect to the muscles of the upper extremity with a strong emphasis on those that connect to the muscles in the forearm and hand.

- Muscles need to get stronger throughout your entire body but mostly those of the fingers, arms, shoulders, and core.

- Rock climbing taxes your cardiovascular system mostly in the forearms, hands, and fingers. It’s unlikely therefore that you will ever obtain your maximum heart rate while rock climbing. Your cardiovascular system must deliver plenty of oxygen to the muscles in your forearms and transport waste products away. The more efficiently this process works, the better you can keep on climbing.

The most important question now is of course, how long does it take for these tissues to adapt?

Depending on the tissue involved it takes from a couple of seconds to a couple of minutes to up to 2 years.

Here are the abovementioned structures again, but now organized by adaptation speed:

- The neurological system can adapt within seconds to minutes to become more efficient in transmitting signals. More about this in chapter 3 of this article

- Hypertrophy of muscles is a process that starts to become visible from 6 weeks onwards

- Improvements in cardiovascular fitness are noticeable in around 8-12 weeks

- Tendons (thickness and stiffness), ligaments, and bones (density) can take up to 2 years to reach the required/necessary improvement

With this overview, you have an idea of what is happening to your body at the initial phase of your rock climbing journey. Of course, all the adaptations continue after the initial two years but at a reduced speed.

2. Mental Adaptation

The mental aspect of rock climbing is huge.

It is usually given far less attention though, than the physical and technical aspects. Yes, it is the overall “joker” in the sport. The “make it or break it” factor. And it plays an enormous role in defining how often you should climb as a beginner.

Why is that?

Because of the following 2 reasons:

- You will have to deal with the different fears that you’re likely to experience as a climber: fear of falling, fear of heights, fear of failing, and fear of not training enough. They all inhibit your progress and can alter or destabilize your movement. Thereby increasing the chance of injuries like flexor tendon tenosynovitis or climber elbow.

- You will also have to learn to observe your body and mind and use their signals accordingly. This mental asset can help you greatly in recognizing when to climb and how intense, and when a break is best.

A classic example of how fear of falling can alter climbing performance is one I experienced recently on a route where I’m forced to climb well passed the bolt I need to clip before I can do so efficiently. The fear of falling results in me tensioning my body, over-gripping (holding onto hand holds harder than necessary and thus wasting energy), moving rigidly, having shaky legs, reduced precision in foot placement, increased heart rate, and sweaty fingers. This all inhibits my brain from learning fluid movements and the correct amount of force necessary for the moves I need to do. The fact that I’m using excess force and that I’m moving rigidly increases the likelihood of acute overload and of me positioning my body inefficiently, which both increase the chances of injury.

For me, the key to mental adaptation is to accept these fears and to deal with them head-on but cut them up into pieces. So, I climb to the last clipped quick draw and fall. Then 30 centimeters higher I fall again and continue doing so until I’m at the point where I used to be afraid but now less so. Once this fear has been reduced in my head, I can start to focus better on my climbing.

The bottom line is that as a beginning rock climber, it’s essential for your long-term injury-free progress that you develop a strong inner awareness early on. This means you become aware of how fit you feel (to decide if you can climb), how you move (to improve technique), and that you recognize fears and deal with them before they affect your climbing and may harm you.

3. Skill Development: Motor Learning Explained

Rock climbing is mainly a technique-based sport. The better your technique the more efficiently you climb. You’ll figure this out quickly when you see “weak-looking” people climb hard routes.

So, how do you learn rock climbing technique? What happens to your body and brain when you try new movement patterns?

That’s what we’ll dive into now.

First off, let’s discuss motor learning. This is your nervous system’s capacity to learn new movements, or motor patterns because that’s what they really are. New combinations of neurons fire together to elicit novel movements.

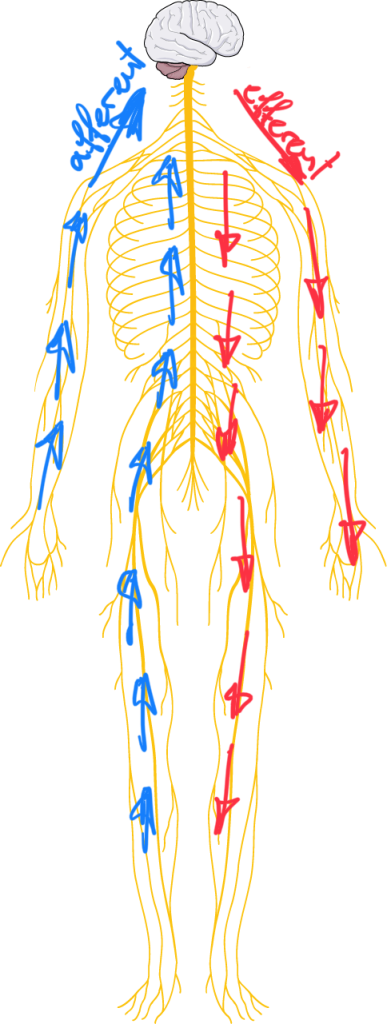

This goes as follows: your brain perceives the need to move your body and limbs into a position to grab the next hold. This perception comes from nerve signals that come from various locations in your body toward the brain (afferent nerve signaling). Among these origins of afferent nerve signals are your eyes, fingers, feet, and balance organ.

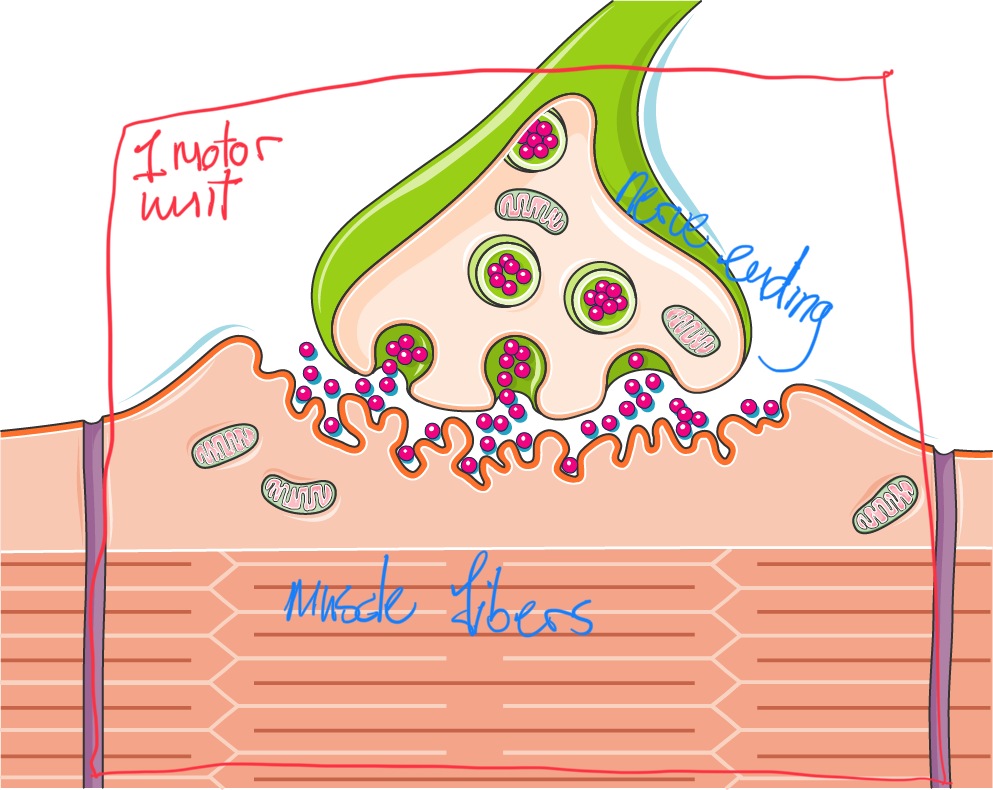

Once your brain has processed these signals, it responds by sending signals toward the body (efferent nerve signaling). These signals go through motor units (the nerve ends that connect to the muscle) to all the muscles in your body, generating the movements necessary to grab the next hold.

Or not, and then you fall.

This then leads to motor learning; you and your nervous system need to tweak this firing of neurons so that the combination of movement, tension, and relaxation in the collaborating parts of your body will make you better capable to reach the hold on your next try.

The collaboration between muscles is called intermuscular coordination, and the collaboration and optimization of individual motor units on the same muscle are called intra-muscular coordination.

Complex movement patterns like rock climbing moves require so many things to fall in place that, logically, you need this process of trial and error for your nervous system to tweak its function. Every time you try a motor pattern this process becomes more efficient. Which in turn leads to more efficient movement, better tension and relaxation, and less energy consumption.

There are a couple of ways that are known to efficiently learn new motor patterns:

- Chunking: separating complex motor patterns into smaller chunks to learn them. This is what you do when you boulder a sport route from bolt to bolt to learn the moves, or when on a boulder problem you try each move separately.

- Chaining: chaining chunks of a movement pattern together so that you develop a motor pattern. On the wall, this is called “linking” the route where you start climbing increasingly larger parts until you can do it entirely.

- Regression: doing easier variations of a move you’re trying to do. In rock climbing, this could mean doing the same move on bigger holds or on a wall that’s less steep.

- Progression: progressing from the bigger holds on a vertical wall to a more overhanging wall, whereafter you also reduce the hold size.

These are strategies you can apply every time you engage on a route where you encounter parts you can’t do or can’t do efficiently.

The bottom line of rock climbing skill development is that your nervous system has as many moves as possible preprogrammed to automatically execute the right moves at the right moment when you climb a new route. The best way to get this large movement repertoire as a beginning rock climber is to climb the largest variety of routes that you can.

4. Preventing Overuse Injuries as a Beginning Rock Climber

The biggest reason you can’t climb daily as a beginning rock climber is the risk of overuse injuries. As you understand by now, you must develop novel motor patterns and a mind that’s comfortable with heights. Both of these cause you to climb inefficiently at a start which in turn causes a bigger load on your body. Thus, as a beginning rock climber, you must give your tissues enough time to recover from previous rock-climbing sessions.

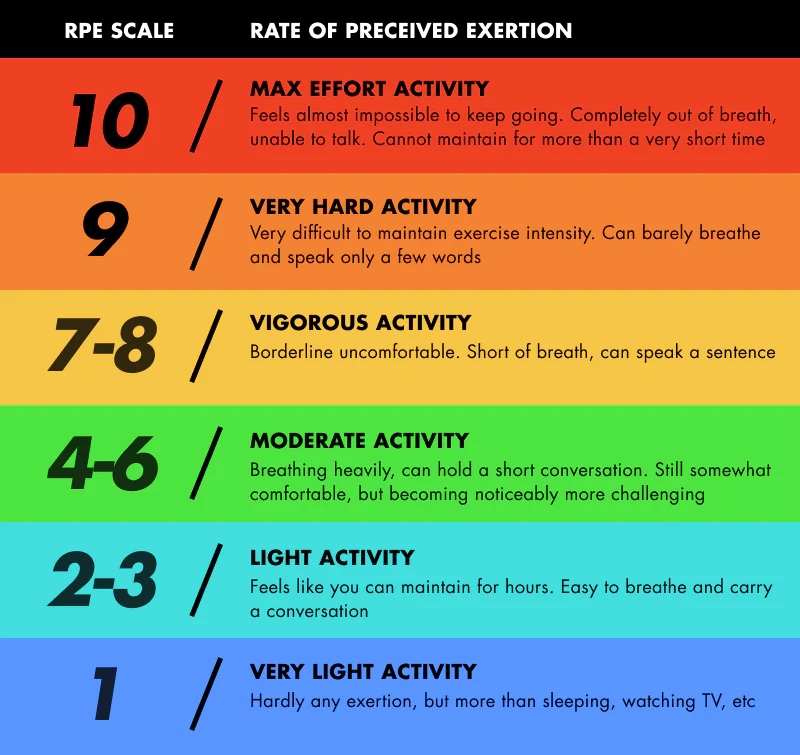

You can use the following guidelines to decide when you can climb again by measuring your Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) after each climbing session. You can do this by giving your level of exhaustion after a session a rating from 1-10. Where 1 is no exhaustion at all and 10 means you’re empty.

- RPE 1 – 4: you could climb again tomorrow

- RPE 5 – 7: you could climb again the day after tomorrow

- RPE 8 – 10: You could climb again in 3-4 days

It’s important to always check on the day you want to climb if it’s a good idea. If you’re still exhausted from your last session, it’s better to rest another day.

Once you’ve been climbing for >2 Years you can climb more days in a row by alternating the type of climbing you do. How you plan these training sessions is a topic for another blog though.

Besides timing your climbing sessions correctly it’s also important to consider the following to optimize recovery and prevent overuse injuries:

- Never climb through pain

- If an unknown pain keeps returning for more than a week, contact a healthcare professional

- Drink half an ounce of fluid per pound per day and additionally drink 2x your body weight in kg in milliliters every 15-20 minutes during training sessions.

- Find the right type of nutrition for your body, preferably with a trained (sports) nutritionist to ensure you consume the right quantity and type of calories

5. Time & Energy Availability

This is one I struggle with often. Unfortunately, work, life, and rock climbing all use the same battery in my body. So, if other aspects of life demand a lot of energy I have less available for rock climbing. Even when I’d wish it to be different.

This is something to deal with and not ignore. If you force your climbing on a low battery you run an increased risk of overuse injuries and overtraining syndrome.

As you can measure your RPE after a training session, you can ask yourself: “How fresh do you feel?” on a scale from 0-10. This is a good starting point to discover how ready you are to climb. I suggest you use the number you give yourself as follows:

- Freshness 0-4: don’t train at all, rest another day

- Freshness 5-7: you can climb but reduce your training intensity

- Freshness 8-10: climb as you wish

Freshness is not a scientific measurement but a starting point to discover your readiness for training. It doesn’t need to mean the same to you as it does to your climbing buddy. If it always means the same thing to you though, it is something you can use to make an informed decision.

6. Is Climbing Once a Week Enough?

With everything we have discussed, it’s now easy to answer this question. As a beginner rock climber, climbing once a week will never be too much but it’s also not enough for optimal progression. As things go, you want to climb often and variety of routes to stimulate your nervous system to learn new motor patterns.

Thus, if you can only climb once a week, that’s fine. If you can climb more, that would be better.

So, now back to the initial question, how often should you climb as a beginner rock climber?

7. How Often Should Beginners Climbers Climb?

As I mentioned at the start of this article, beginning climbers should climb 2-3x per week. This is the ideal amount to stimulate the nervous system with new movements while it allows enough time for recovery. At the start, you must always take at least a 1-day break between climbing sessions and use the RPE and Freshness measurements to get an idea of your readiness for exercise right now.