You can climb again after injury if you can move the injured part of your body similarly to the healthy side, pain-free, and you need to be able to load it over a prolonged period. You can test by hanging from 1 or 2 arms if the injury was in the upper limb or by sitting in a full squat or Cossack squat if the injury was in the lower limb. Doing these activities repeatedly will give you a clear idea of your readiness for climbing. The next step would be to slowly return to climbing by climbing well below your redpoint grade and progressing grade by grade and day by day while monitoring your pain levels throughout.

You’ll discover this progression and what to look and feel for in this blog. First, though, we’ll look at the different structures that are prone to injury while rock climbing and how long they take to heal.

Let’s dive right in.

1. Types of Injury & Their Healing Times

Before you discover when you can climb again after injury you should know the type of injury you have and how long the tissue needs to heal. Some injuries require you to thread with more caution than others.

First and foremost, there’s a difference between acute and chronic injuries.

Perhaps a better way to describe chronic injuries is by calling them injuries with a slow onset. You can’t name the moment it started exactly; it just came on slowly. Acute injuries, on the other hand, are usually the result of an accident or an acute overload and you notice pain or discomfort from one moment to the next.

Below I’ll discuss the different structures in the body, how they commonly get injured in rock climbers, and what to expect when you’re asking yourself when you can climb again after injury. Even if you fit a pattern I describe here, talk to a medical professional to understand your injury before you start a rehabilitation protocol.

2.1 Bone

The bones in your body make up your skeleton and are hard and can either break (fracture) or bruise. How it comes to a fracture differs. These are the 4 most common ways to injure a bone as a rock climber:

- Fracture: usually due to a high impact from a fall in rock climbing. For example, you can suffer an ankle or foot fracture after falling from a boulder or slamming into the wall during sports climbing.

- Stress fracture: stress fractures are a result of continuous overload. This can happen to the carpal bones in the hand for example. A stress fracture of the hook of the hamatum is a common one. And in younger climbers between the ages of 12-15 epiphysial stress fractures in the fingers are common. That’s where the tendons connect to the bone and are not fully hardened out at this age.

- Bruise: a bone bruise happens due to a dull impact. Depending on the severity a bruise can last up to a year to heal. It can also hurt quite a while longer than a broken bone.

- Blood circulation issues; Panner’s Disease f.e.: blood circulation issues of bones like Panner’s Disease are uncommon and not well understood. In the case of Panner’s Disease, there’s an issue with the blood circulation in the distal humerus causing pain in the elbow and is thought to occur due to repeated stress in the area. These issues require rest, a lot of it. If not treated accordingly, the bone can lose its blood supply, leading to tissue necrosis. Which is a nice way to say that the bone tissue dies.

2.2 Tendon

Tendons are stiff and collagen-rich tissues that connect muscles to bones. Due to the low metabolism in tendons, they’re slow to respond to changes in load. This makes tendons prone to overload injuries because you only notice pain or discomfort sometime after you overload the tissue. It also makes them slow to heal from injuries. Where an inflammation phase of a muscle or capsule lasts 5-7 days, that of a tendon around 14 days. And this is true for healing phases.

These are the 3 most common tendon injuries:

- Tendinopathy: a disturbance of the construction and destruction of tendinous tissue. This imbalance leads to tiny injuries in the tendon and is always caused by overload. Typical tendinopathies seen in rock climbers are climbers’ elbow, tennis elbow, biceps tendinopathy, triceps tendinopathy, and tendinopathy of the flexor tendon. There can be inflammation, which then makes it tendonitis. Healing time: up to 2 years. It depends mostly on the time until you started treatment and confounding factors like muscle weakness and mobility issues in surrounding joints.

- Tendon strain: due to an acute injury. The tendon fibers are still intact but hurt. Healing time: 3 months.

- Tendon tear (partial or complete): due to a more intense acute injury. Some or all tendon fibers are torn. Healing time: around 2 years. It depends on the size of the tear how much your ability to climb again after injury will be reduced.

2.3 Muscle

Muscles make our body move and have good blood circulation, they respond well to load. The most common muscle injuries in rock climbers are:

- Muscle strain: same as for tendons. The muscle fibers are intact but hurt. Healing time: +- 3 weeks.

- Muscle tear (partial or complete): again, same as with tendons. Due to a more intense acute injury. Some or all muscle fibers are torn. Healing time: small tear 6 weeks. Big tear 3-4 months. Complete tear requires surgery and counts with a healing time of around 6 months.

- Trigger points: occur due to overload, underload, or because of reduced blood circulation. This can happen following prolonged compression. For example, your climbing harness pressing on your gluteal musculature. Healing time: if treated correctly 1-6 weeks depending on confounding factors.

2.4 Ligament

Ligaments are passive structures that prevent excessive movements in joints. If you twist your ankle, tear a pulley ligament, or dislocate your shoulder you strain or tear the ligaments in that area. For ligaments to heal well, you should evade movements that stretch the tissue. Because the shorter the ligamentous tissue the better it can prevent excessive movement.

Ligament injuries are:

- Ligament strain: similar to muscle. Healing times: 6-8 weeks.

- Ligament tear (either partial or complete): same as muscle. Healing times: partial tear 3-6 months, complete tear requires surgery and recovery can last up to a year.

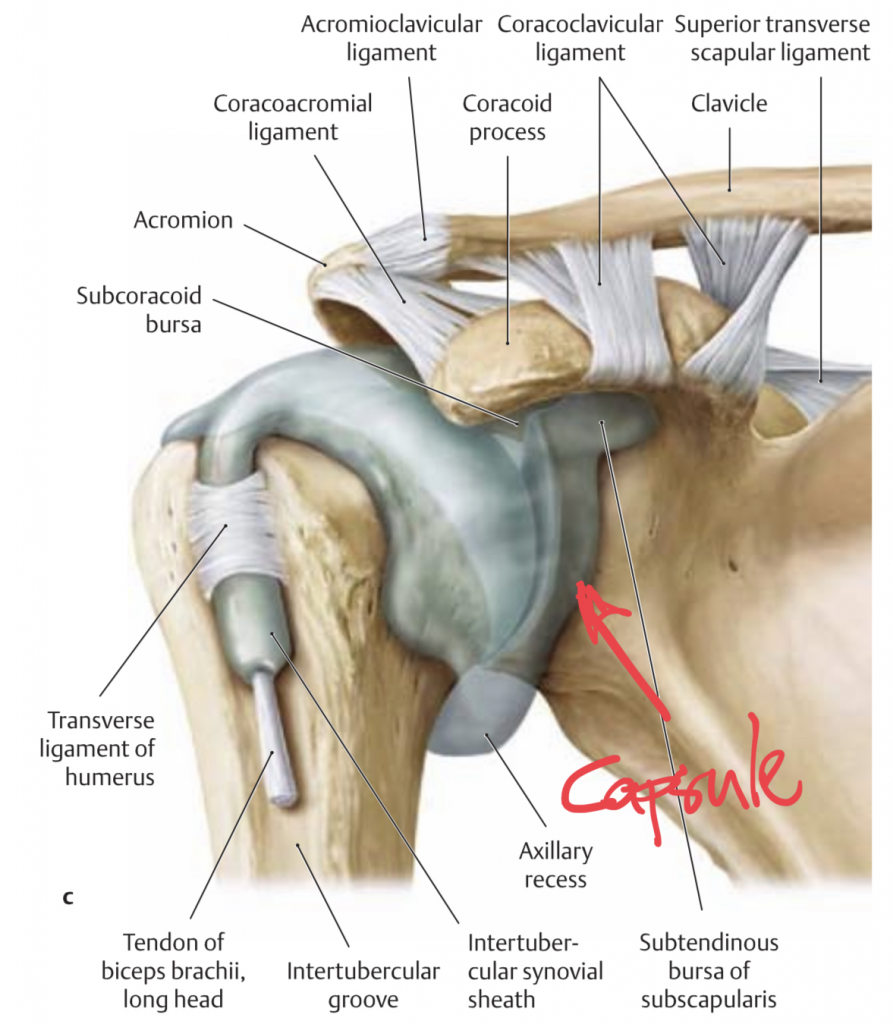

Typical ligament injuries are anterior cruciate ligament, medial collateral ligament, or lateral collateral ligament injuries in the knee. Or in the shoulder the acromioclavicular ligament.

2.5 Capsule

A capsule is a sac that holds joint ends together and contains a liquid that helps to nourish the joint cartilage. promotes fluid movement. Ligaments are usually part of the capsule; thus, I’ll mention only two capsule-specific injuries here:

- Capsulitis (inflammation of the capsule): the capsule and or the synovial fluid can irritate and inflame. This inflammation then causes swelling, pain, and mobility reduction. If the synovial fluid in the capsule is inflamed it’s called synovitis. Healing time: around 3 months.

- Capsule stiffness: occurs because of inactivity. Capsule stiffness is often secondary to another injury. For example, because of Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain. This pain causes you to not lift the arm to which the capsule responds by stiffening. A stiff capsule can hurt with or without inflammation. The latter is called adhesive capsulitis or frozen shoulder. Healing times: frozen shoulder 1 and a half to 2 years. Normal capsule stiffness is 1-3 months depending on the severity.

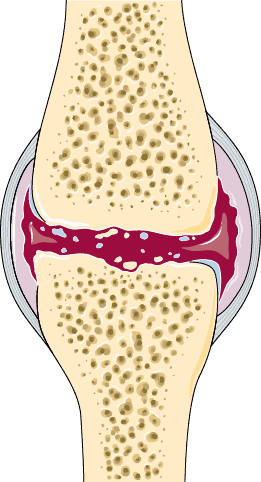

2.6 Cartilage

Cartilage is a softer type of bone that you find at the end of each bone and that makes up the joint surfaces. Cartilage helps to absorb shock forces. Or in the case of the labrum in the shoulder and hip, and the meniscus in the knee, it adds stability. These are the injuries of the cartilage:

- Labral tear: very common in rock climbers and often a consequence of (sub-)luxation of the shoulder. Several types of SLAP Tears are more or less invasive in shoulder function. You can recover without surgery if the labrum is stable and doesn’t inhibit normal joint function. Healing time: 6 months.

- Cartilage tears: happen due to sheer, rotational, or high-impact forces. In this category, you’ll find meniscus tears. You can recover without surgery if the tear doesn’t inhibit normal joint function. Healing time: 6-9 months.

- Osteoarthritis: auto-immune disorder where water-containing proteins in the cartilage tissue lose their capacity to hold water. This dehydrates the cartilage, making it less shock-absorbing and more prone to damage. Chances of osteoarthritis increase with age, level of physical activity (too much or too little), smoking, overweight, underweight, and many other factors. Osteoarthritis can exist in your joints without you noticing it. So, that’s a good thing. If it does cause you problems though, you can often resolve your pain with physiotherapy. If pain persists and joint function doesn’t come back a joint replacement surgery might be an option. Healing time: with surgery around a year, without surgery around 6 months.

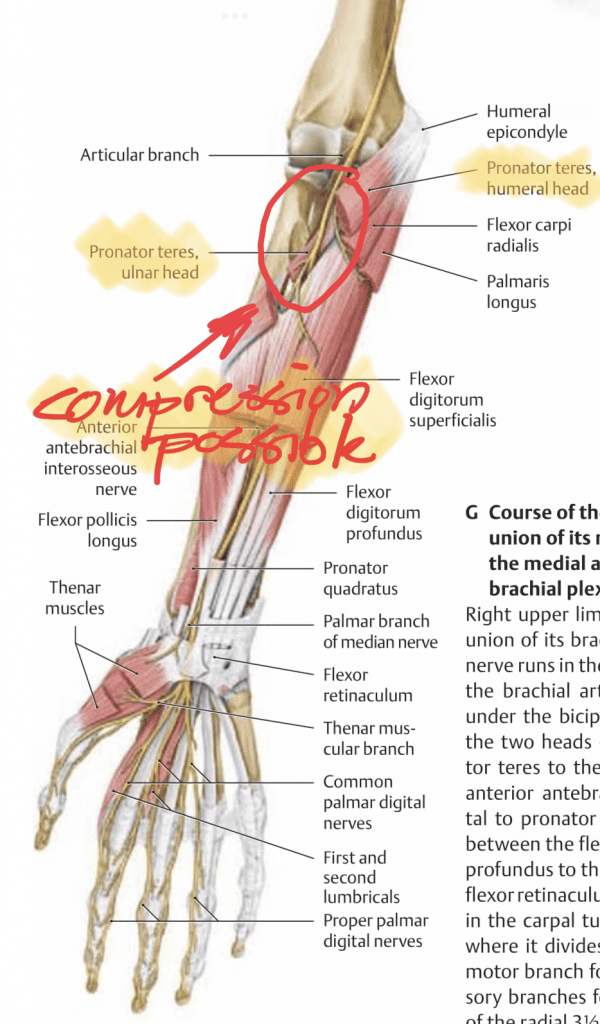

2.7 Nerve

Nerves conduct electric signals from the brain to the body and vice versa. Nerves only break when you pass a sharp surface by them or with severe injuries where a bone splinter cuts a nerve. Otherwise, nerves are more susceptible to compression. These are the injuries of the nerves:

- Neuropathy: disease of the peripheral nerves of the body. The origin of peripheral neuropathy can be anything from alcoholism to auto-immune disorders, to gluten sensitivity and vitamin deficiencies. Neuropathies can come on fast or slow and may or may not be reversible.

- Neuropraxia: is a compression of the nerve which reduces signal conduction. With this injury, there’s no actual damage to the nerve. Neuropraxia can be the result of your harness compressing the sciatic nerve or due to hypertension in muscles where nerves pass through or by. A good example in rock climbers would be the median nerve passing through the pronator teres muscle. If you release the compression on the nerve it should recover within 3 months.

- Axonotmesis: in this case, the myelin sheath (a protective and conduction-enhancing layer around nerves) is cut. Yet, the nerve itself is intact and can continue to transmit signals. It appears that axons farther away from the spine and central nervous system heal faster than the ones closer to the spine. The more peripheral axons heal in 4-5 weeks and the more proximal ones in 1-2 years. That’s on a microscopical level though, for your strength and/or sensitivity to return completely can take longer.

- Neurotmesis: the nerve is entirely cut and there’s no signal conduction possible. This can happen during surgery or an accident. If it’s a small nerve innervating a small sensory area of the skin, it might not be as devastating. However, if a nerve innervating the muscles of the foot is cut you might experience severe impairments. In this case, surgery to reconnect the nerves might be an idea. It depends on the location of the nerve and how fast the recovery will be.

2.8 Intervertebral Disc

Intervertebral discs absorb shock forces in the spine and aid movement in all directions. The discs are made from a fibrous border called the annulus fibrosis, filled with a jelly liquid called the nucleus pulposis. Monotonous loading of the spine in a single direction can cause the jelly substance to press against the border. When this starts to bulge outward it can compress the spinal nerves. These are the injuries of the intervertebral disc:

- Partial tear/disc bulging: you might or might not notice a partial tear. If it is degenerative and never compresses a nerve root you might never notice anything of it. Still, a disc issue can stimulate nociceptors (alarm signal nerve fibers that your brain uses to help you experience pain), and thus cause pain. It depends on the quality of your joints and muscle around the injured disc and how fast you recover. Count with a recovery of at least 6-8 weeks.

- Complete tear/herniated disc: a herniated disc causes at least pain when moving in a certain direction, if not continuous, along a dermatome (the part of the skin that corresponds to the affected nerve root). The only reason to do surgery on an intervertebral disc is either when you experience paralysis or complete loss of sensation in a dermatome or if you experience pain you can’t handle. Otherwise, conservative therapy is indicated. A herniated disc takes up to 2 years to heal but you’ll likely be able to climb normally between 6-12 months after you herniated the disc.

Natural healing times are super important metrics during rehabilitation. Still, all by themselves, they’re not sufficient to guide decision-making. If your tendon should be healed according to the natural healing times but it still hurts while climbing way below your regular climbing grade, you can’t progress. That’s why you should always combine the information I discussed so far with functional milestones. Can you move your joint pain-free through its entire range of motion? Like raising your arms overhead or bending your knee fully. And can you do a full squat or hang on two arms? With this information, you can decide better if and how you should climb.

2. Functional Milestones to Climb Again After Injury

These are the groups of functional milestones for rehabilitation to climb again after injury. The best way would be to compare them to normative values derived from large databases containing the physical prerequisites for rock climbers to climb a certain grade. Mostly this is not the case these are not available. though so you can compare the injured and healthy sides.

- Full Pain-free range of motion of the joint(s) in the affected area

- Isolated strength of affected movements at least 90-95% of healthy side

And then the climbing-specific milestones.

For upper body injuries:

- Hanging horizontally with 2 arms with feet on the floor for 15 seconds

- Hanging horizontally with 1 arm with feet on the floor for 15 seconds

- Dead hanging from 2 arms for 15 seconds

- Dead hang from 1 arm for 15 seconds

For finger injuries, the functional milestones are different than the rest of the upper body injuries. For those, I recommend using a hangboard to test your readiness for climbing. Start at the biggest most comfortable hold and hang for 15 seconds with feet touching the floor. If this is comfortable hang without feet touching the floor. Test every 2 weeks to see if you can hang onto a smaller hold than the one you’re comfortable at. The holds you can hang from without pain, you can climb on.

For lower body injuries:

- Sitting in a full squat

- Performing multiple full squats consecutively

- Sitting in a pigeon stretch

- Pressing foot down in a pigeon stretch

- Sitting in a Cossack squat

- Performing multiple Cossack squats consecutively

3. Important Take-Aways

Knowing your readiness to climb again after injury is the delicate balance between the:

- Understanding your pain

- Being aware of natural healing times

- Progressively loading the injured structures to force them to heal appropriately

- Using climbing-specific parameters to get an idea of your climbing capacity of the wall

- Once you’re on the wall; understand your body’s limits at the moment and climb accordingly (grades, types of moves, steepness, types of holds, number of routes)